Why Christian Conservatives Often Confuse Enterprise with Tyranny

EDITOR'S NOTE: As the dust settles on the ever-shifting landscapes of the economy and politics, Christian conservatives stand at a crossroads. On one side, a historical embrace of free markets and on the other, an emerging distrust of private enterprise — a sentiment not exclusive to them. The venerable World Magazine, a beacon for conservatives, is caught in this tempest, weaving narratives that paint markets with the same tyrannical brush as governments. Such equivocation is not just intellectually hazardous; it’s a misdiagnosis of our socio-economic ailments. The lines between corporate decisions and governmental overreach are blurring, with critics misinterpreting the symptoms of crony capitalism for the inherent evils of the market. As the gap widens between the ideologies of free markets and perceived threats of capitalism, it's essential to dissect these arguments with precision lest we lose sight of the real enemy: unchecked government power. Welcome to the crossfire of capitalism, where the battle is as much about perception as it is about policy.

Christian conservatives, for the most part, are relatively receptive to free markets, or at least a generalized concept of what used to be called free enterprise. (This is as opposed to a lot of evangelical economists teaching at Christian colleges that embrace socialism in one form or another as THE Christian version of economics.)

World Magazine has been on the relatively conservative side of political affairs, or at least enough so to be scorned by faculty members of more progressives Christian colleges, but it also has the tendency to give into the conservative notion that free market economies need to be regulated for both legal and cultural reasons. In a recent edition, Brad Littlejohn warned Christians to beware of the “tyranny” of free markets, claiming that markets are as tyrannical as governments, a claim that should not go unchallenged.

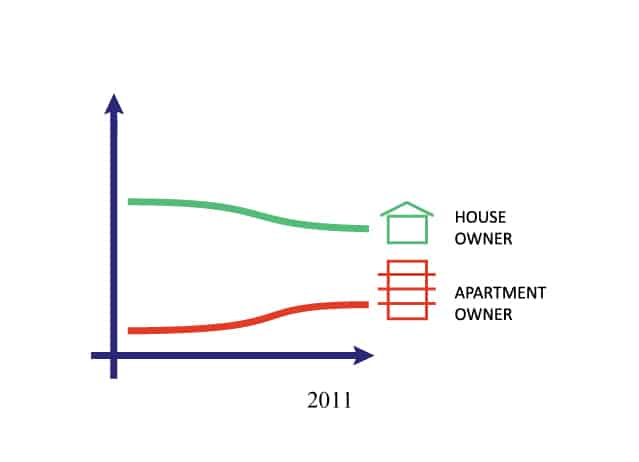

We should note that for the past few years, conservatives have become increasingly hostile toward private enterprise, some of it corresponding with the rise of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives within larger companies, a movement that, frankly, has turned into a racket. However, as much hostility is shown toward normal trade, not just free trade overseas but also the outcomes of private exchange within our economy.

For example, Tucker Carlson and other well-known conservatives have attacked private enterprise for a number of alleged sins. As I wrote a few years ago:

Capitalism creates poverty. Capitalism has stolen our future. Capitalism ravages the planet. Capitalism oppresses us. Capitalism needs to be controlled by government or it will throw most of us into poverty and misery and enrich only the well-placed few.

These are not missives from The Nation or the Daily Worker, although no doubt the writers from those publications would share the sentiments. No, these diatribes against the market economy come from the American Conservative. Of course, it is hardly the only conservative publication that rails against the market system, as First Things can also be counted on to speak out against the evils of an economy based on private property, a price system, and profit and loss. For that matter, before it fell to the grim reaper, the Weekly Standard also raised its voice against markets. Pat Buchanan has been railing against free trade and free markets for years.

Thus, Littlejohn’s piece in World hardly falls into a vacuum, as he quotes the strongly anti-capitalist writer Sohrab Ahmari, who writes in Tyranny, Inc., “that private actors can imperil freedom just as much as overweening governments.” Given that governments have engaged in unprecedented massive and murderous atrocities over the past 120 years, private enterprise must meet a very “high” bar, indeed, to match such malevolence.

Littlejohn writes:

Although many on the right may not have noticed until their own core values were threatened, paycheck-to-paycheck workers in many industries find themselves largely at the mercy of powerful employers, who, using convoluted contracts drafted by armies of lawyers, can put their employees in “submission holds” where they have little choice but to comply. Ahmari documents the proliferation of phenomena like mandatory arbitration, noncompete clauses, and more to show the ways in which most workers in America no longer enjoy anything like the “freedom of contract” once celebrated as the hallmark of free-market capitalism.

The solution lies not in seeking either some Marxist or libertarian utopia in which perfect economic balance and harmony is reestablished. Rather, we must recognize, Ahmari contends, that “coercion is inevitable in human affairs, not least the significant portions of our lives we spend as workers and consumers. A political-economic order that would wish away this truth only allows coercion to proliferate unchallenged.”

The problem here should be obvious: Littlejohn (quoting Ahmari) confuses organizational behavior with the give-and-take of market behavior, but even giving him that much still leaves confused thinking. Even if one believes that business organizations engage in coercive behavior toward employees, that so-called coercion is not the same as governmental action. Businesses are not governments.

For one, while a business may set conditions of employment that one may choose to reject – with the consequence being fired from a job – that hardly is the same thing as governmental coercion. A business cannot arrest someone, nor can it imprison or perform executions. In short, a business may limit one’s choices in matters relating to the firm itself, but it cannot limit freedom the way that governments do every day.

While one can decry some of the censorship on social media or a bank refusing an account to someone whose political views are not progressive, one should also see the connection between these businesses and governments with which they are intertwined. Many of these firms simply are carrying out the wishes of progressive governments and their agencies, crony capitalism at work.

For example, the recent ruling against the FBI for its involvement in pressuring social media firms became big new precisely because a federal agency with coercive powers made sure that private firms played ball with the government. Moreover, neither Ahmari nor Littlejohn have addressed the fact that much of American business today is tied in one way to government authorities, either through regulation or by being a vendor.

These relationships make a difference especially when a private firm is carrying out a government diktat, as we saw with the FBI and Twitter. Moreover, there also can be consequences for private firms that make politically-based decisions such as what happened to the CEO of a bank that closed the account of British politician Nigel Farage because she disagreed with his political views. Conversely, no one from the FBI or any other federal agency was tossed into the unemployment lines when news of their misconduct became known.

This isn’t just about firms engaging in politicized behavior. Markets are the best antidote for behavior that consumers might abhor, the boycott of Bud Light because the company’s marketing director tried to use the product to make a political statement being an excellent example.

We cannot boycott the FBI, CIA, IRS, or any other government agency. The FBI didn’t lose authority when the federal judge forbade its agents to pressure social media to speak the government line. Furthermore, government agents can arrest you, torture and even kill someone and not be punished, even if there is no reasonable justification for their actions.

Surely one can be saddened at the rise of woke capitalism, the spread of divisive Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) seminars in company workplaces, and the growing symbiotic ties between businesses and the political elites.

But there still is a world of difference between what a private firm can do and what government agencies do on a regular basis when it comes to violating human rights. That popular Christian writers like Littlejohn and Ahmari cannot see the difference is cause for alarm.

Originally published by William L. Anderson at Mises Institute